Here is Susan Sontag’s 58-point treatise that defines the term “camp” and that arguably brought it into mainstream use. For the full essay, visit here.

1. To start very generally: Camp is a certain mode of aestheticism. It is one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon. That way, the way of Camp, is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization.

2. To emphasize style is to slight content, or to introduce an attitude which is neutral with respect to content. It goes without saying that the Camp sensibility is disengaged, depoliticized — or at least apolitical.

3. Not only is there a Camp vision, a Camp way of looking at things. Camp is as well a quality discoverable in objects and the behavior of persons. There are “campy” movies, clothes, furniture, popular songs, novels, people, buildings. . . . This distinction is important. True, the Camp eye has the power to transform experience. But not everything can be seen as Camp. It’s not all in the eye of the beholder.

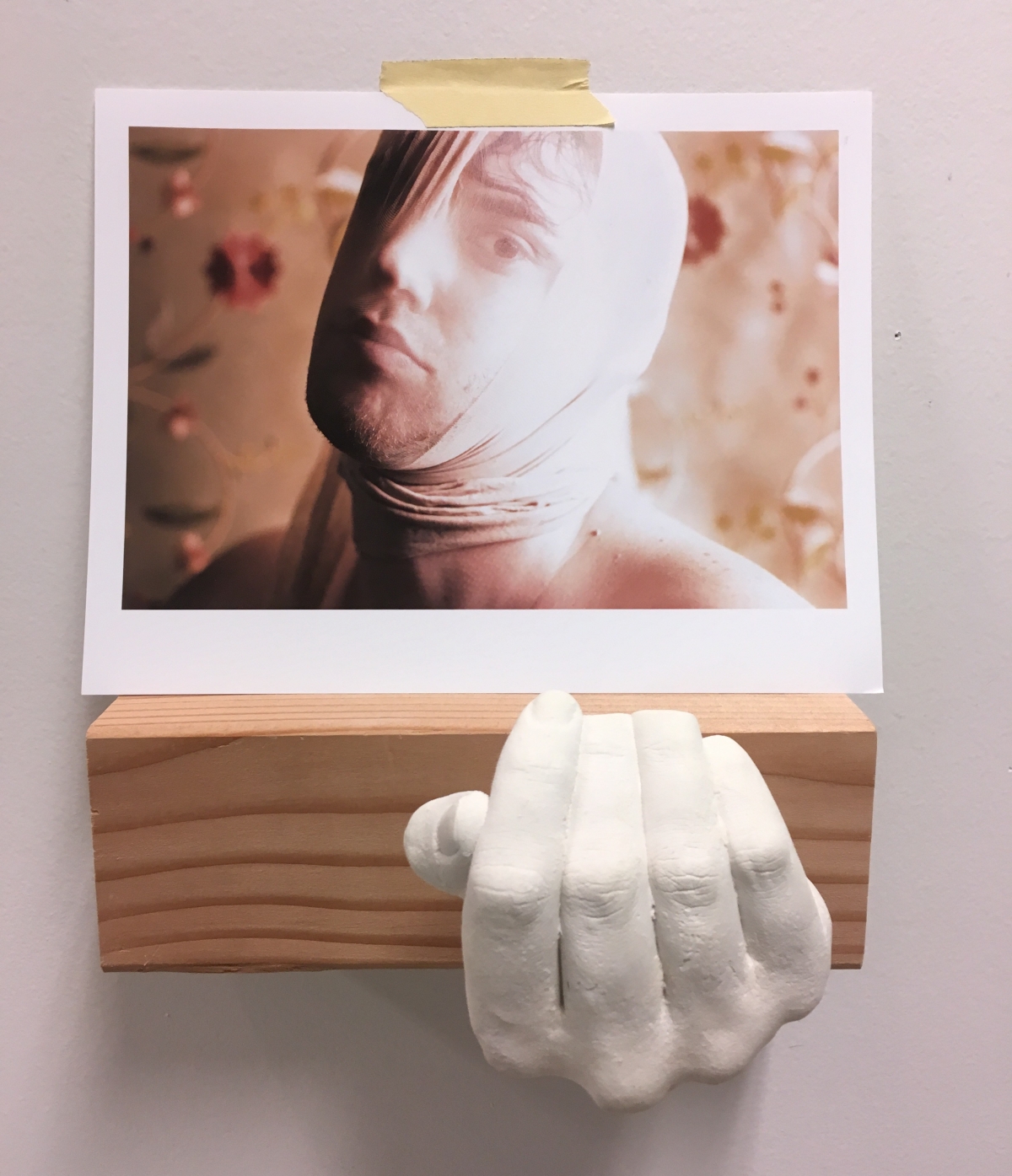

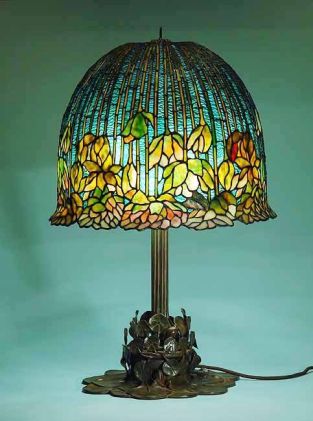

4. Random examples of items which are part of the canon of Camp:

Zuleika Dobson

Tiffany lamps

Scopitone films

The Brown Derby restaurant on Sunset Boulevard in LA

The Enquirer, headlines and stories

Aubrey Beardsley drawings

Swan Lake

Bellini’s operas

Visconti’s direction of Salome and ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore

certain turn-of-the-century picture postcards

Schoedsack’s King Kong

the Cuban pop singer La Lupe

Lynn Ward’s novel in woodcuts, God’s Man

the old Flash Gordon comics

women’s clothes of the twenties (feather boas, fringed and beaded dresses, etc.)

the novels of Ronald Firbank and Ivy Compton-Burnett

stag movies seen without lust

5. Camp taste has an affinity for certain arts rather than others. Clothes, furniture, all the elements of visual décor, for instance, make up a large part of Camp. For Camp art is often decorative art, emphasizing texture, sensuous surface, and style at the expense of content. Concert music, though, because it is contentless, is rarely Camp. It offers no opportunity, say, for a contrast between silly or extravagant content and rich form. . . . Sometimes whole art forms become saturated with Camp. Classical ballet, opera, movies have seemed so for a long time. In the last two years, popular music (post rock-‘n’-roll, what the French call yé yé) has been annexed. And movie criticism (like lists of “The 10 Best Bad Movies I Have Seen”) is probably the greatest popularizer of Camp taste today, because most people still go to the movies in a high-spirited and unpretentious way.

6. There is a sense in which it is correct to say: “It’s too good to be Camp.” Or “too important,” not marginal enough. (More on this later.) Thus, the personality and many of the works of Jean Cocteau are Camp, but not those of André Gide; the operas of Richard Strauss, but not those of Wagner; concoctions of Tin Pan Alley and Liverpool, but not jazz. Many examples of Camp are things which, from a “serious” point of view, are either bad art or kitsch. Not all, though. Not only is Camp not necessarily bad art, but some art which can be approached as Camp (example: the major films of Louis Feuillade) merits the most serious admiration and study.

7. All Camp objects, and persons, contain a large element of artifice. Nothing in nature can be campy . . . Rural Camp is still man-made, and most campy objects are urban. (Yet, they often have a serenity — or a naiveté — which is the equivalent of pastoral. A great deal of Camp suggests Empson’s phrase, “urban pastoral.”)

8. Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style — but a particular kind of style. It is the love of the exaggerated, the “off,” of things-being-what-they-are-not. The best example is in Art Nouveau, the most typical and fully developed Camp style. Art Nouveau objects, typically, convert one thing into something else: the lighting fixtures in the form of flowering plants, the living room which is really a grotto. A remarkable example: the Paris Métro entrances designed by Hector Guimard in the late 1890s in the shape of cast-iron orchid stalks.

9. As a taste in persons, Camp responds particularly to the markedly attenuated and to the strongly exaggerated. The androgyne is certainly one of the great images of Camp sensibility. Examples: the swooning, slim, sinuous figures of pre-Raphaelite painting and poetry; the thin, flowing, sexless bodies in Art Nouveau prints and posters, presented in relief on lamps and ashtrays; the haunting androgynous vacancy behind the perfect beauty of Greta Garbo. Here, Camp taste draws on a mostly unacknowledged truth of taste: the most refined form of sexual attractiveness (as well as the most refined form of sexual pleasure) consists in going against the grain of one’s sex. What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine; what is most beautiful in feminine women is something masculine. . . . Allied to the Camp taste for the androgynous is something that seems quite different but isn’t: a relish for the exaggeration of sexual characteristics and personality mannerisms. For obvious reasons, the best examples that can be cited are movie stars. The corny flamboyant female-ness of Jayne Mansfield, Gina Lollobrigida, Jane Russell, Virginia Mayo; the exaggerated he-man-ness of Steve Reeves, Victor Mature. The great stylists of temperament and mannerism, like Bette Davis, Barbara Stanwyck, Tallulah Bankhead, Edwige Feuillière.

10. Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a “lamp”; not a woman, but a “woman.” To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater.

11. Camp is the triumph of the epicene style. (The convertibility of “man” and “woman,” “person” and “thing.”) But all style, that is, artifice, is, ultimately, epicene. Life is not stylish. Neither is nature.

12. The question isn’t, “Why travesty, impersonation, theatricality?” The question is, rather, “When does travesty, impersonation, theatricality acquire the special flavor of Camp?” Why is the atmosphere of Shakespeare’s comedies (As You Like It, etc.) not epicene, while that of Der Rosenkavalier is?

13. The dividing line seems to fall in the 18th century; there the origins of Camp taste are to be found (Gothic novels, Chinoiserie, caricature, artificial ruins, and so forth.) But the relation to nature was quite different then. In the 18th century, people of taste either patronized nature (Strawberry Hill) or attempted to remake it into something artificial (Versailles). They also indefatigably patronized the past. Today’s Camp taste effaces nature, or else contradicts it outright. And the relation of Camp taste to the past is extremely sentimental.

14. A pocket history of Camp might, of course, begin farther back — with the mannerist artists like Pontormo, Rosso, and Caravaggio, or the extraordinarily theatrical painting of Georges de La Tour, or Euphuism (Lyly, etc.) in literature. Still, the soundest starting point seems to be the late 17th and early 18th century, because of that period’s extraordinary feeling for artifice, for surface, for symmetry; its taste for the picturesque and the thrilling, its elegant conventions for representing instant feeling and the total presence of character — the epigram and the rhymed couplet (in words), the flourish (in gesture and in music). The late 17th and early 18th century is the great period of Camp: Pope, Congreve, Walpole, etc, but not Swift; les précieux in France; the rococo churches of Munich; Pergolesi. Somewhat later: much of Mozart. But in the 19th century, what had been distributed throughout all of high culture now becomes a special taste; it takes on overtones of the acute, the esoteric, the perverse. Confining the story to England alone, we see Camp continuing wanly through 19th century aestheticism (Bume-Jones, Pater, Ruskin, Tennyson), emerging full-blown with the Art Nouveau movement in the visual and decorative arts, and finding its conscious ideologists in such “wits” as Wilde and Firbank.

15. Of course, to say all these things are Camp is not to argue they are simply that. A full analysis of Art Nouveau, for instance, would scarcely equate it with Camp. But such an analysis cannot ignore what in Art Nouveau allows it to be experienced as Camp. Art Nouveau is full of “content,” even of a political-moral sort; it was a revolutionary movement in the arts, spurred on by a Utopian vision (somewhere between William Morris and the Bauhaus group) of an organic politics and taste. Yet there is also a feature of the Art Nouveau objects which suggests a disengaged, unserious, “aesthete’s” vision. This tells us something important about Art Nouveau — and about what the lens of Camp, which blocks out content, is.

16. Thus, the Camp sensibility is one that is alive to a double sense in which some things can be taken. But this is not the familiar split-level construction of a literal meaning, on the one hand, and a symbolic meaning, on the other. It is the difference, rather, between the thing as meaning something, anything, and the thing as pure artifice.

17. This comes out clearly in the vulgar use of the word Camp as a verb, “to camp,” something that people do. To camp is a mode of seduction — one which employs flamboyant mannerisms susceptible of a double interpretation; gestures full of duplicity, with a witty meaning for cognoscenti and another, more impersonal, for outsiders. Equally and by extension, when the word becomes a noun, when a person or a thing is “a camp,” a duplicity is involved. Behind the “straight” public sense in which something can be taken, one has found a private zany experience of the thing.

18. One must distinguish between naïve and deliberate Camp. Pure Camp is always naive. Camp which knows itself to be Camp (“camping”) is usually less satisfying.

19. The pure examples of Camp are unintentional; they are dead serious. The Art Nouveau craftsman who makes a lamp with a snake coiled around it is not kidding, nor is he trying to be charming. He is saying, in all earnestness: Voilà! the Orient! Genuine Camp — for instance, the numbers devised for the Warner Brothers musicals of the early thirties (42nd Street; The Golddiggers of 1933; … of 1935; … of 1937; etc.) by Busby Berkeley — does not mean to be funny. Camping — say, the plays of Noel Coward — does. It seems unlikely that much of the traditional opera repertoire could be such satisfying Camp if the melodramatic absurdities of most opera plots had not been taken seriously by their composers. One doesn’t need to know the artist’s private intentions. The work tells all. (Compare a typical 19th century opera with Samuel Barber’s Vanessa, a piece of manufactured, calculated Camp, and the difference is clear.)

20. Probably, intending to be campy is always harmful. The perfection of Trouble in Paradise and The Maltese Falcon, among the greatest Camp movies ever made, comes from the effortless smooth way in which tone is maintained. This is not so with such famous would-be Camp films of the fifties as All About Eve and Beat the Devil. These more recent movies have their fine moments, but the first is so slick and the second so hysterical; they want so badly to be campy that they’re continually losing the beat. . . . Perhaps, though, it is not so much a question of the unintended effect versus the conscious intention, as of the delicate relation between parody and self-parody in Camp. The films of Hitchcock are a showcase for this problem. When self-parody lacks ebullience but instead reveals (even sporadically) a contempt for one’s themes and one’s materials – as in To Catch a Thief, Rear Window, North by Northwest — the results are forced and heavy-handed, rarely Camp. Successful Camp — a movie like Carné’s Drôle de Drame; the film performances of Mae West and Edward Everett Horton; portions of the Goon Show — even when it reveals self-parody, reeks of self-love.

21. So, again, Camp rests on innocence. That means Camp discloses innocence, but also, when it can, corrupts it. Objects, being objects, don’t change when they are singled out by the Camp vision. Persons, however, respond to their audiences. Persons begin “camping”: Mae West, Bea Lillie, La Lupe, Tallulah Bankhead in Lifeboat, Bette Davis in All About Eve. (Persons can even be induced to camp without their knowing it. Consider the way Fellini got Anita Ekberg to parody herself in La Dolce Vita.)

22. Considered a little less strictly, Camp is either completely naive or else wholly conscious (when one plays at being campy). An example of the latter: Wilde’s epigrams themselves.

23. In naïve, or pure, Camp, the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails. Of course, not all seriousness that fails can be redeemed as Camp. Only that which has the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve.

24. When something is just bad (rather than Camp), it’s often because it is too mediocre in its ambition. The artist hasn’t attempted to do anything really outlandish. (“It’s too much,” “It’s too fantastic,” “It’s not to be believed,” are standard phrases of Camp enthusiasm.)

25. The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers. Camp is the paintings of Carlo Crivelli, with their real jewels and trompe-l’oeil insects and cracks in the masonry. Camp is the outrageous aestheticism of Steinberg’s six American movies with Dietrich, all six, but especially the last, The Devil Is a Woman. . . . In Camp there is often something démesuré in the quality of the ambition, not only in the style of the work itself. Gaudí’s lurid and beautiful buildings in Barcelona are Camp not only because of their style but because they reveal — most notably in the Cathedral of the Sagrada Familia — the ambition on the part of one man to do what it takes a generation, a whole culture to accomplish.

26. Camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is “too much.” Titus Andronicus and Strange Interlude are almost Camp, or could be played as Camp. The public manner and rhetoric of de Gaulle, often, are pure Camp.

27. A work can come close to Camp, but not make it, because it succeeds. Eisenstein’s films are seldom Camp because, despite all exaggeration, they do succeed (dramatically) without surplus. If they were a little more “off,” they could be great Camp – particularly Ivan the Terrible I & II. The same for Blake’s drawings and paintings, weird and mannered as they are. They aren’t Camp; though Art Nouveau, influenced by Blake, is.

28. Again, Camp is the attempt to do something extraordinary. But extraordinary in the sense, often, of being special, glamorous. (The curved line, the extravagant gesture.) Not extraordinary merely in the sense of effort. Ripley’s Believe-It-Or-Not items are rarely campy. These items, either natural oddities (the two-headed rooster, the eggplant in the shape of a cross) or else the products of immense labor (the man who walked from here to China on his hands, the woman who engraved the New Testament on the head of a pin), lack the visual reward – the glamour, the theatricality – that marks off certain extravagances as Camp.

29. The reason a movie like On the Beach, books like Winesburg, Ohio and For Whom the Bell Tolls are bad to the point of being laughable, but not bad to the point of being enjoyable, is that they are too dogged and pretentious. They lack fantasy. There is Camp in such bad movies as The Prodigal and Samson and Delilah, the series of Italian color spectacles featuring the super-hero Maciste, numerous Japanese science fiction films (Rodan, The Mysterians, The H-Man) because, in their relative unpretentiousness and vulgarity, they are more extreme and irresponsible in their fantasy – and therefore touching and quite enjoyable.

30. Of course, the canon of Camp can change. Time has a great deal to do with it. Time may enhance what seems simply dogged or lacking in fantasy now because we are too close to it, because it resembles too closely our own everyday fantasies, the fantastic nature of which we don’t perceive. We are better able to enjoy a fantasy as fantasy when it is not our own.

31. This is why so many of the objects prized by Camp taste are old-fashioned, out-of-date, démodé. It’s not a love of the old as such. It’s simply that the process of aging or deterioration provides the necessary detachment — or arouses a necessary sympathy. When the theme is important, and contemporary, the failure of a work of art may make us indignant. Time can change that. Time liberates the work of art from moral relevance, delivering it over to the Camp sensibility. . . . Another effect: time contracts the sphere of banality. (Banality is, strictly speaking, always a category of the contemporary.) What was banal can, with the passage of time, become fantastic. Many people who listen with delight to the style of Rudy Vallee revived by the English pop group, The Temperance Seven, would have been driven up the wall by Rudy Vallee in his heyday.

32. Camp is the glorification of “character.” The statement is of no importance – except, of course, to the person (Loie Fuller, Gaudí, Cecil B. De Mille, Crivelli, de Gaulle, etc.) who makes it. What the Camp eye appreciates is the unity, the force of the person. In every move the aging Martha Graham makes she’s being Martha Graham, etc., etc. . . . This is clear in the case of the great serious idol of Camp taste, Greta Garbo. Garbo’s incompetence (at the least, lack of depth) as an actress enhances her beauty. She’s always herself.

33. What Camp taste responds to is “instant character” (this is, of course, very 18th century); and, conversely, what it is not stirred by is the sense of the development of character. Character is understood as a state of continual incandescence – a person being one, very intense thing. This attitude toward character is a key element of the theatricalization of experience embodied in the Camp sensibility. And it helps account for the fact that opera and ballet are experienced as such rich treasures of Camp, for neither of these forms can easily do justice to the complexity of human nature. Wherever there is development of character, Camp is reduced. Among operas, for example, La Traviata (which has some small development of character) is less campy than Il Trovatore(which has none).

34. Camp taste turns its back on the good-bad axis of ordinary aesthetic judgment. Camp doesn’t reverse things. It doesn’t argue that the good is bad, or the bad is good. What it does is to offer for art (and life) a different — a supplementary — set of standards.

35. Ordinarily we value a work of art because of the seriousness and dignity of what it achieves. We value it because it succeeds – in being what it is and, presumably, in fulfilling the intention that lies behind it. We assume a proper, that is to say, straightforward relation between intention and performance. By such standards, we appraise The Iliad, Aristophanes’ plays, The Art of the Fugue, Middlemarch, the paintings of Rembrandt, Chartres, the poetry of Donne, The Divine Comedy, Beethoven’s quartets, and – among people – Socrates, Jesus, St. Francis, Napoleon, Savonarola. In short, the pantheon of high culture: truth, beauty, and seriousness.

36. But there are other creative sensibilities besides the seriousness (both tragic and comic) of high culture and of the high style of evaluating people. And one cheats oneself, as a human being, if one has respect only for the style of high culture, whatever else one may do or feel on the sly.

37. The first sensibility, that of high culture, is basically moralistic. The second sensibility, that of extreme states of feeling, represented in much contemporary “avant-garde” art, gains power by a tension between moral and aesthetic passion. The third, Camp, is wholly aesthetic.

38. Camp is the consistently aesthetic experience of the world. It incarnates a victory of “style” over “content,” “aesthetics” over “morality,” of irony over tragedy.

39. Camp and tragedy are antitheses. There is seriousness in Camp (seriousness in the degree of the artist’s involvement) and, often, pathos. The excruciating is also one of the tonalities of Camp; it is the quality of excruciation in much of Henry James (for instance, The Europeans, The Awkward Age, The Wings of the Dove) that is responsible for the large element of Camp in his writings. But there is never, never tragedy.

40. Style is everything. Genet’s ideas, for instance, are very Camp. Genet’s statement that “the only criterion of an act is its elegance”2 is virtually interchangeable, as a statement, with Wilde’s “in matters of great importance, the vital element is not sincerity, but style.” But what counts, finally, is the style in which ideas are held. The ideas about morality and politics in, say, Lady Windemere’s Fan and in Major Barbara are Camp, but not just because of the nature of the ideas themselves. It is those ideas, held in a special playful way. The Camp ideas in Our Lady of the Flowers are maintained too grimly, and the writing itself is too successfully elevated and serious, for Genet’s books to be Camp.

41. The whole point of Camp is to dethrone the serious. Camp is playful, anti-serious. More precisely, Camp involves a new, more complex relation to “the serious.” One can be serious about the frivolous, frivolous about the serious.

42. One is drawn to Camp when one realizes that “sincerity” is not enough. Sincerity can be simple philistinism, intellectual narrowness.

43. The traditional means for going beyond straight seriousness – irony, satire – seem feeble today, inadequate to the culturally oversaturated medium in which contemporary sensibility is schooled. Camp introduces a new standard: artifice as an ideal, theatricality.

44. Camp proposes a comic vision of the world. But not a bitter or polemical comedy. If tragedy is an experience of hyperinvolvement, comedy is an experience of underinvolvement, of detachment.

45. Detachment is the prerogative of an elite; and as the dandy is the 19th century’s surrogate for the aristocrat in matters of culture, so Camp is the modern dandyism. Camp is the answer to the problem: how to be a dandy in the age of mass culture.

46. The dandy was overbred. His posture was disdain, or else ennui. He sought rare sensations, undefiled by mass appreciation. (Models: Des Esseintes in Huysmans’ À Rebours, Marius the Epicurean, Valéry’s Monsieur Teste.) He was dedicated to “good taste.”

47. Wilde himself is a transitional figure. The man who, when he first came to London, sported a velvet beret, lace shirts, velveteen knee-breeches and black silk stockings, could never depart too far in his life from the pleasures of the old-style dandy; this conservatism is reflected in The Picture of Dorian Gray. But many of his attitudes suggest something more modern. It was Wilde who formulated an important element of the Camp sensibility — the equivalence of all objects — when he announced his intention of “living up” to his blue-and-white china, or declared that a doorknob could be as admirable as a painting. When he proclaimed the importance of the necktie, the boutonniere, the chair, Wilde was anticipating the democratic esprit of Camp.

48. The old-style dandy hated vulgarity. The new-style dandy, the lover of Camp, appreciates vulgarity. Where the dandy would be continually offended or bored, the connoisseur of Camp is continually amused, delighted. The dandy held a perfumed handkerchief to his nostrils and was liable to swoon; the connoisseur of Camp sniffs the stink and prides himself on his strong nerves.

49. It is a feat, of course. A feat goaded on, in the last analysis, by the threat of boredom. The relation between boredom and Camp taste cannot be overestimated. Camp taste is by its nature possible only in affluent societies, in societies or circles capable of experiencing the psychopathology of affluence.

50. Aristocracy is a position vis-à-vis culture (as well as vis-à-vis power), and the history of Camp taste is part of the history of snob taste. But since no authentic aristocrats in the old sense exist today to sponsor special tastes, who is the bearer of this taste? Answer: an improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals, who constitute themselves as aristocrats of taste.

51. The peculiar relation between Camp taste and homosexuality has to be explained. While it’s not true that Camp taste is homosexual taste, there is no doubt a peculiar affinity and overlap. Not all liberals are Jews, but Jews have shown a peculiar affinity for liberal and reformist causes. So, not all homosexuals have Camp taste. But homosexuals, by and large, constitute the vanguard — and the most articulate audience — of Camp. (The analogy is not frivolously chosen. Jews and homosexuals are the outstanding creative minorities in contemporary urban culture. Creative, that is, in the truest sense: they are creators of sensibilities. The two pioneering forces of modern sensibility are Jewish moral seriousness and homosexual aestheticism and irony.)

52. The reason for the flourishing of the aristocratic posture among homosexuals also seems to parallel the Jewish case. For every sensibility is self-serving to the group that promotes it. Jewish liberalism is a gesture of self-legitimization. So is Camp taste, which definitely has something propagandistic about it. Needless to say, the propaganda operates in exactly the opposite direction. The Jews pinned their hopes for integrating into modern society on promoting the moral sense. Homosexuals have pinned their integration into society on promoting the aesthetic sense. Camp is a solvent of morality. It neutralizes moral indignation, sponsors playfulness.

53. Nevertheless, even though homosexuals have been its vanguard, Camp taste is much more than homosexual taste. Obviously, its metaphor of life as theater is peculiarly suited as a justification and projection of a certain aspect of the situation of homosexuals. (The Camp insistence on not being “serious,” on playing, also connects with the homosexual’s desire to remain youthful.) Yet one feels that if homosexuals hadn’t more or less invented Camp, someone else would. For the aristocratic posture with relation to culture cannot die, though it may persist only in increasingly arbitrary and ingenious ways. Camp is (to repeat) the relation to style in a time in which the adoption of style — as such — has become altogether questionable. (In the modem era, each new style, unless frankly anachronistic, has come on the scene as an anti-style.)

54. The experiences of Camp are based on the great discovery that the sensibility of high culture has no monopoly upon refinement. Camp asserts that good taste is not simply good taste; that there exists, indeed, a good taste of bad taste. (Genet talks about this in Our Lady of the Flowers.) The discovery of the good taste of bad taste can be very liberating. The man who insists on high and serious pleasures is depriving himself of pleasure; he continually restricts what he can enjoy; in the constant exercise of his good taste he will eventually price himself out of the market, so to speak. Here Camp taste supervenes upon good taste as a daring and witty hedonism. It makes the man of good taste cheerful, where before he ran the risk of being chronically frustrated. It is good for the digestion.

55. Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation – not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy. It only seems like malice, cynicism. (Or, if it is cynicism, it’s not a ruthless but a sweet cynicism.) Camp taste doesn’t propose that it is in bad taste to be serious; it doesn’t sneer at someone who succeeds in being seriously dramatic. What it does is to find the success in certain passionate failures.

56. Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of “character.” . . . Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as “a camp,” they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.

57. Camp taste nourishes itself on the love that has gone into certain objects and personal styles. The absence of this love is the reason why such kitsch items as Peyton Place (the book) and the Tishman Building aren’t Camp.

58. The ultimate Camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful . . . Of course, one can’t always say that. Only under certain conditions, those which I’ve tried to sketch in these notes.

Here’s a picture of Rita standing in front of Kyle’s interactive projection piece. That was something I thought was really cool, and it was also really fun to engage with. Just standing next to it, I was confused about what it was, as all I saw was a still projection and a strange looking thing on the ground where it was coming from. It was only after walking in front of it you realized it was fragmenting the environment, projecting geometric fractals of whatever crossed its path.

Here’s a picture of Rita standing in front of Kyle’s interactive projection piece. That was something I thought was really cool, and it was also really fun to engage with. Just standing next to it, I was confused about what it was, as all I saw was a still projection and a strange looking thing on the ground where it was coming from. It was only after walking in front of it you realized it was fragmenting the environment, projecting geometric fractals of whatever crossed its path.

Where can we find those camps? John Waters, the Connoisseur of Camp, was said to have even been offended by the mere mention of the word “camp” in a recent

Where can we find those camps? John Waters, the Connoisseur of Camp, was said to have even been offended by the mere mention of the word “camp” in a recent